A Note To Readers

Ours is an age, apparently, of short attention spans. I am thus compelled to note that of this book’s 400-hundred-plus pages, its chapters — the story you’re here to read — occupy fewer than three hundred.

It’s not necessary to read any of those other 100-plus pages. Seriously.

At the end of many paragraphs you will see a small number. That’s a note. No need to read those; you’ll be fine without them.

If you’re a notes geek, however, lucky is the geek reading digitally: tap to open note. Finished? Tap anywhere.(Special note to my fellow historians: in an ebook, the notes are always at the bottom of the page.)

As ever: thanks for reading. I appreciate it.

PROLOGUE: CHILDREN OF PLENTY

The white Europeans who colonized North America’s eastern coast in the seventeenth century encountered extraordinary abundance. Immense bird flocks blackened the sky. Rivers and streams ran thick with fish. Shorelines teemed with crab and turtle, and forests with deer, bear, and other game.

Above all, there was land, millions of acres stretching off into a distance that would require many lifetimes to map and measure.

Of all the cultural shocks that rattled colonists’ psyches, this was perhaps the greatest. They had emigrated from societies where land was scarce and ownership limited. Not so in North America, where land abundance enabled them to develop a meat-centered diet on a scale that the Old World could neither imagine nor provide.

In the earliest years, settlers trapped, snared, shot, netted, and feasted on venison, squirrel, and lobster; pigeon, pheasant, and possum. But they wanted more. Civilized people ate civilized food: beef, mutton, and pork. Civilized people exercised dominion over not just land but animals, too, especially cattle, sheep, and swine.

To the men and women who settled North America, the idea of a world without livestock was as peculiar, and dangerous, as the notion of a world without God. Therein lay the road to savagery.

And Europeans had not traveled halfway around the world to emulate the natives they encountered in North America. According to one chronicler, those “savages” “[ran] over the grass” like “foxes and wild beasts,” leaving “the land untilled” and “the cattle not settled.” Native villages contained neither pen nor barn.

This lack of “civilized” markers doomed the “savage people.” Because they “inclose[d] no ground” and kept no “cattell,” decreed Massachusetts leader John Winthrop, they forfeited any claim to the land and its wealth. Instead, white Europeans would rule and use the land to produce meat, thereby demonstrating the superiority of their culture.

Colonists’ imported cattle thrived beyond belief or expectation. One South Carolinian boasted that his colony was so “advantageously . . . scituated, that there [was] little or no need of Providing Fodder for Cattle in the Winter.”

As for hogs, those “swarm like Vermine upon the Earth,” grumbled one man. From north to south, hogs snuffled through forest floors carpeted with acorns and other mast, growing fat on nature’s bounty and multiplying to the point of nuisance. The result was that colonial Americans never wanted for ham, bacon, and sausage.

Livestock translated into tangible wealth that, with good management, multiplied more readily than silver or gold. In Maryland in the late 1600s, one cow and a calf carried as much monetary value as six or seven hundred pounds of tobacco, a third of a year’s crop for one man.

Settlers also valued meat for its nutritional qualities.

Meat is water, protein, and fat, all of which humans require for survival. More precisely, it is the tissue from which muscle is constructed. Content proportions depend on the age, size, and species of the animal, but a general average is 75 percent water, 20 percent protein, and 5 percent fat.

Nowadays, fat suffers an undeserved bad reputation, but it’s one of the body’s most efficient tools for storing energy; stored fat fueled early hominids’ flights from danger and protected them when food was scarce. Anglo-American colonists also favored meat because it was less labor intensive than foods that required planting, hoeing, and harvesting.

Water, which all flesh contains, nurtures mold and bacteria; meat must be eaten immediately or preserved.

Colonists pounded chicken to a paste, stuffed it into ceramic pots, and sealed the container with a layer of fat or oil. They dried beef in the sun, and salted, pickled, and smoked fresh pork. (Colonial diets tended to be porkcentric not only because hogs abounded but because pork is much easier to preserve than beef.)

Abundance and desire translated into meat on the table.

Statistics are hard to come by — the era predated census bureaus and questionnaires — but evidence compiled by historians allows a broad generalization: the average white colonial ate more food, and especially more meat, than anyone on the planet (aside from queens, czars, and other exceptionally privileged persons).

Across Europe, a non-royal was lucky to see meat once or twice a week. A typical colonial adult male, in contrast, put away about two hundred pounds a year. (Enslaved people were chronically underfed and ate less of every kind of food.)

Anecdotal evidence supports the estimates.

A man who visited Pennsylvania in the 1750s marveled at the abundance of beef cattle. “[E]ven in the humblest or poorest houses, no meals are served without a meat course.” Servants accustomed to scraps and scraping by in the Old World assumed and expected hefty meat rations in the New.

One visitor recorded an encounter with an indentured servant who had run away “because he thought he ought to have meat every day” and his master refused to cooperate.

Another servant, William Clutton, threatened to strike. It was the “Custom of [the] Country for servants to have meat 3 times a week,” but his skinflint master, one Thomas Beale, served only rations of bread and cheese.

Officials charged Clutton with mutiny and sedition, but when he was hauled to court, Master Beale’s cheapskatery backfired: several people testified that Clutton was a “very honest civill [sic] person.” He paid his court costs and walked free, presumably headed back to work and the meat to which he believed he was entitled.

Over time, carnivorous paradise begot lethal legacy. The abundance of meat spawned waste and fostered indifference bordering on cruelty. “The Cattle of Carolina are very fat in Summer,” charged one critic, but bone bags in winter because their owners refused to protect them from “cold Rains, Frosts, and Snows.”

Settlers dismissed such criticisms, claiming they could spare neither time nor labor to build animal shelters or fencing, occupied as they were with “too many other Affairs.” (That their free-roaming livestock placed them on the same plane as the natives they despised was an irony white settlers chose to ignore.)

As a result, cattle and hogs scattered their droppings hither and yon, left uncollected because no one would spare the labor to gather and spread them on corn and tobacco fields.

As years passed and settlers exhausted and overgrazed their land, they simply moved on to fresh ground. And why not? In the New World, millions of acres lay just over the horizon.

Thus developed a cycle of destructive extravagance that Americans would pass from one generation to the next. Abundance of land nurtured an abundance of the livestock that enabled settlers to eat well and to accumulate tangible wealth with a minimal investment of labor.

The more livestock a household owned, the more secure its financial future, and the more meat-centric its diet. The more meat-centric the expectations, the more land they wanted, especially for cattle: a single adult bovine required anywhere from five to twenty grazing acres.

Livestock lust fractured communities.

William Bradford, Pilgrim leader at Plymouth, Massachusetts, complained that “no man now thought he could live except he had cattle and a great deal of ground to keep them.”

“[T]here was no longer any holding [settlers] together.” They needed “great lots,” in order to keep cattle. As a result, his people “were scattered all over the Bay” and their original settlement lay “thin and . . . desolate.”

Bradford feared cattle lust would bring “the Lord’s displeasure” down on them and “be the ruin of New England.”

And not only the Lord’s. As whites migrated in search of fresh meadow and forest for their livestock, cattle tromped through natives’ patches of beans and squash, and hogs rooted up their caches of corn. Some white settlers deliberately set animals loose in order to push Indians deeper into the interior.

A member of the Narragansett tribe voiced a common grievance: Once upon a time the tribe had luxuriated in an abundance of “deer and skins.” No more. Now “the English” had stolen the land and allowed “their cows and horses [to] eat the grass; and their hogs [to] spoil [the] clam banks.”

“Your hogs & Cattle injure Us,” lamented another man in 1666. “You come too near Us to live & drive Us from place to place. We can fly no farther.”

He begged the Maryland legislature to “let [his people] know where to live & how to be secured for the future from the Hogs & Cattle.”

The answer? Nowhere. Courts refused to listen to natives’ complaints; colonial assemblies ignored treaties.

Natives in their turn used whites’ desire for livestock against their enemy. In encounter after encounter, Indians stole, slaughtered, tortured, and mutilated livestock, because doing so struck at the heart of what it meant to be white and European.

When a group of Narragansetts seized one white man, they forced him to watch as they killed five of his cattle. “[W]hat will Cattell now doe you good?” they asked.

Another group warned that they stood prepared to fight. “You must consider,” they told their white foes, “the Indians lost nothing but their life; you must lose your fair houses and cattle.”

The two years of ambush, torching, and retribution that followed that encounter left seven thousand Indians dead as compared to three thousand whites. But the natives slaughtered eight thousand head of whites’ cattle.

Other livestock-driven battles would follow, but whites would win the war. They would convert large chunks of the continent into a livestock trail epic in size and in its demands on the land and its people.

As the decades passed, colonists gradually abandoned hands-off livestock husbandry in favor of more deliberate, commercial production, thanks to two lures.

The first was urban growth along the colonial seaboard. Towns and cities were few, but their inhabitants needed food. The second was the lucrative intracoastal and international trade in barreled meats, available to them because they were British colonials.

In New-York, Philadelphia, and other port towns, commission agents and ship owners dispatched cattle near and far. To the southernmost Atlantic coast colonies, where landowners devoted land and enslaved labor to tobacco, and preferred to let others raise beef on their behalf. To Caribbean-based British and French plantations. To England and Europe as food for growing populations there.

One colonial cattle and hog economy flourished in the valley of the Potomac South Branch River in what is now the northeastern corner of West Virginia.

The area consisted of fertile bottomland suitable for planting, and hills thick with forage grass. In summer, South Branch farmers grew corn in the lowlands while cattle grazed upland. Come fall, they cut cornstalks to the ground, leaving the ears intact, and piled the “shocks” throughout their fields for cattle feed.

As stock fed, they deposited manure (including corn; they could not digest the kernels), which provided fertilizer for the next growing season. Once the cattle had devoured the shocks in a field, hands led them to a new location and fresh stocks, and herded hogs into the first field. The porcines snuffled up the leavings, including the corn kernels, and deposited their own manure.

Settlers planted this corn-cattle-hog complex along the central Atlantic seaboard, modifying it to suit local climate, terrain, and soil. By the time white Americans rebelled against their colonial overlords, many regarded access to meat, especially beef, as a mark of being an American, an entitlement. To that end, over the next two centuries, they built an American way of meat designed to accommodate this right.

And as we will see, Americans were prepared to pay any price for that American plenty.

PART I. BUILDING AN AMERICAN WAY OF MEAT

CHAPTER 1: CARNIVORE AMERICA

In early 1822, eleven-year-old Phineas T. Barnum (1810- 1891) was hired to help drive cattle from his home in rural Connecticut to New-York City. The boy had heard of the fabled York, as it was then called. No country corner, it was a proper city (population 124,000), situated on an island, no less, and surely full of wonders. Now he would visit.

Off he went with the drover and the other hands. The group likely traveled a heavily trafficked cattle road that ran parallel to the Hudson River, all the way down to King’s Bridge, where they crossed from the mainland to the northern end of Manhattan Island.

From there they traveled south another ten or so miles along the Boston/Bowery Road to the northernmost fringe of the city, where they stopped at the Bull’s Head tavern at Canal Street, the place where livestock sellers and buyers ate, drank, and conducted business on behalf of the stomachs of York.

Barnum’s crew settled the cattle in a stockyard, and themselves at the Bull’s Head. And then P.T. had five days to explore the city before his crew returned to Connecticut.

He spent the first few days shopping, as Americans did, using coin and barter to obtain (and discard) a variety of items, including a top, a knife, oranges, and firecrackers. Having thus depleted his coin and goods, he devoted the rest of his time to the (free) pleasure that is urban sightseeing.

Among York’s attractions were its famed public markets, of which there were nine when Barnum visited. The smallest were conducted in the centers of selected streets, and consisted of a long string of covered stalls and tables. The biggest were grand brick affairs, often two stories and sometimes covering an entire block. Immense openings on all four sides accommodated the thousands bustling through every morning.

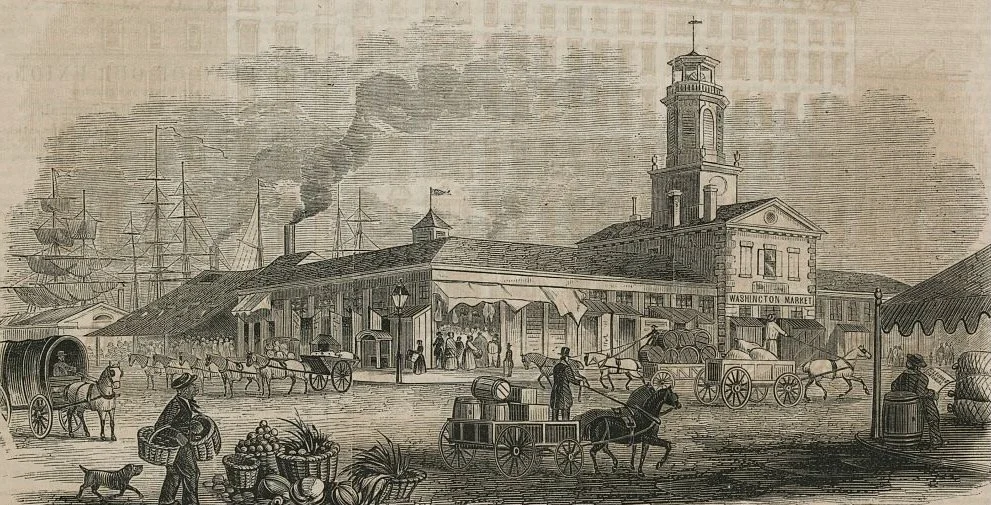

An 1851 rendering of one of the city’s most famed markets, Washington. By the Early 1850s, Wholesalers had taken over the facility. As can be seen, the market sat close to the Hudson River as evidenced by the masts in the background. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

The attraction was food. Row after row of stalls, tables, and counters stacked, piled, and covered, with food:

Oysters, lobster, shrimp. All manner of fish. Fresh produce during the growing season; root vegetables in cold weather while supplies lasted. Chickens, pheasants, and other fowl; ham, sausages, and dried beef. Eggs, cheese, butter, and milk (the latter the most perishable of foods).

And fresh meat, especially beef.

Butchers’ stalls offered a wonderland of fleshy viand. Beef sides and quarters hung from iron hooks. Piles of steaks and ribs, roasts and loins awaited shoppers. Behind their counters, butchers cut meats to order for customers waiting in line.

Young Phineas was flabbergasted. He’d never seen so much fresh meat — and beef, no less!

He was a country boy, and country folk didn’t eat fresh beef. A cow carcass served up hundreds of pounds of meat, too much for a single household, and too valuable to withhold from an urban market whose denizens expected fresh beef every day.

To Barnum’s mind and eyes, such “immense quantities of meat” were “incredible.” So incredible that his inner cynic took charge.

“What under heaven do they expect to do with all this meat?” Barnum asked a young man who had joined him on his tours around town.

“They expect to sell it, of course.”

Barnum scoffed.

“They’ll get sucked in then,” he assured his older companion, at age eleven already confident in his ability to spot suckers and scams.

It was impossible “to consume all that beef before doomsday.”

Years later, an older, wiser (and wealthier and famed) Barnum admitted his naiveté. In truth, he wrote in a mid-century memoir, he was the fool. The meat he saw stacked to the heavens was “probably all masticated within the next twenty-four hours.”

A city may seem a strange place to open a history of carnivorous America. But it was cities that prompted Americans to make meat on a grand scale, and sell it at an affordable price. From their efforts would come, eventually, all the things many people love to hate now: antibiotics and factory farms; CAFOs and Big Ag and Big Food.

This history of the American way of meat is built on a salient fact: city dwellers don’t make their own food. They rely on others to do that for them. The more city dwellers there are, the harder farmers must work to feed them; historically, as urban populations grow, farmers’ numbers decline.

To be clear: in 1822, the overwhelming majority of the US population lived in a rural area, and typically on a farm. The nation then boasted 9.6 million inhabitants — roughly the population of 2024 New Jersey, spread over states and territories as far west as the Mississippi River and beyond. Fewer than 700,000 of them lived in a town or city, but they clustered along the Atlantic seaboard from Boston to Baltimore.

In Massachusetts, for example, sixty percent of the population lived in an urban place. Collectively, the residents of New-York, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia represented five percent of the entire US population.

New-York provides an excellent starting point. Think of it as a living laboratory where Americans learned to assemble the acreage, people, skills, tools, and animals necessary to supply a sizable city with fresh meat every day.

In 1822, York was the new nation’s largest and most important urban assemblage. Perched on the southern tip of Manhattan Island just off the coast of New York state, it was surrounded by waterways and harbors, including the mouth of the Hudson River, the main passageway to interior upstate New York.

The city as seen by an artist in 1851. When Barnum visited, Yorkers lived in a dense cluster at the far south end of the island. IMage courtesy of Library of Congress.

White Europeans had occupied the site since the early 1600s, testament to its strategic and military value. When colonial Americans launched a war for independence, the British were quick to capture and occupy York. After all, having built much of island’s fortifications, the Redcoats knew that Manhattan Island was a superb staging ground for their war with the colonials.

After the revolution, the city served, briefly, as the capital of both the United States and New York state. By the 1820s, its financiers, banks, commission houses, docks, wharves, and warehouses were the nation’s most significant.

And New-Yorkers could not begin to feed themselves, let alone the thousands who descended on the city daily for business, pleasure, or to begin new lives as Americans.

In the 1820s, the city consumed 150 pounds of fresh meat, mostly beef, per person per year. That one dietary demand necessitated the delivery and slaughter of tens of thousands of animals a year. Add in ham, sausage, bacon, and dried beef, as well as eggs and milk, potatoes, onions, and tons of wheat — and the magnitude of urban food logistics becomes clear.

Sourcing and delivering foodstuffs was no small matter in a two-mile-an-hour world. Some cattle arrived by ferry, but most walked to Manhattan from the mainland, herded by cow hands like young Barnum. These days, the drover’s trek that he made can be traveled in a few hours (depending on traffic). He and his fellow cattle hands spent days, if not weeks, on the road.

From this distance, it’s also difficult to grasp the chronic sense of uncertainty and urgency that anchored these logistics. In the 1820s, both war and the specter of food scarcity were never far from mind. A well-fed city endures siege better than one that is not. A well-fed city is a stable, peaceful city. A starving city is a riotous mob.

Thus the public markets. People needed to eat well, at a reasonable price, because the city’s security depended on it. As one historian has phrased it, food was a “public good.” Public markets were a fundament of urban security and civil order.

And thus ends this excerpt. I hope you enjoyed it. If so, tell a friend, or, ya know, your bluesky stream. If you hated it, tell me. Please!

Find it at bookshop.org, Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, Kobo.

Paperback, hardcover, and ebook at all locations. Kobo is ebook only.

Thanks for stopping by — and for making books and reading part of your life.