What Sauce Would You Like With Those Nuggets? Regular or Elongated?

/"But I’m a cooperative soul. So. Chicken nuggets."

Read MoreHistorian. Author. Ranter. Idea Junkie.

This a blog. Sort of. I rarely use it anymore.

"But I’m a cooperative soul. So. Chicken nuggets."

Read MoreI stumbled out of the book cave and back into the world, nearly blinded as I ascended from darkness into daylight. ("Oh! Zombies haven't killed everyone yet. The rest of the world's still here. Sun's out! There are people! There are ideas!") and . . .

Read More “The epicure of the future [will] dine upon artificial meat, artificial flour, and artificial vegetables,” and enjoy the delights of “artificial” wines, liquors, and tobacco. (*1)

“The epicure of the future [will] dine upon artificial meat, artificial flour, and artificial vegetables,” and enjoy the delights of “artificial” wines, liquors, and tobacco. (*1)

So concluded a reporter in 1894 after he visited Professor Pierre-Eugène-Marcellin Berthelot at his Parisian apartment. Berthelot was one of the most famous chemists in the world thanks in part to his belief that all organic materials could be synthesized, and thus manufactured and manipulated in a laboratory. Thanks to “synthetic chemistry,” the professor predicted, by the year 2000 human beings would no longer need farm, field, and range because they would manufacture their food rather than rely on “natural growth.”

“Do you mean,” asked the reporter, “that all our milk, eggs, meat, and flour . . . will be made in factories?” “Why not,” Berthelot replied, “if it proves cheaper and better to make the same materials than to grow them?”

“Strange though it may seem,” he added, “the day will come when man will sit down to dine from his toothsome tablet of nitrogenous matter, . . . portions of savory fat, . . . balls of starchy compounds,” and jars of spices and wines, all of them “economically manufactured in his own factories, . . . unaffected by frost, and free from the microbes with which over-generous nature sometimes modifies the value of her gifts.”

Berthelot conceded that the manufacture of steaks and bacon would not be easy, but dismissed the obstacles as nothing more than “chemical problems.” He predicted that artificial meat would be delivered in the form of easy-to-swallow tablets in “any color and shape” that a gourmand desired (tablets, in his view, being an improvement over the original: “the beefsteak of to-day is not the most perfect of pictures in either color or composition.”).

To naysayers, Berthelot pointed out that making steak in a lab was simply an extension of the progress humans had devised for centuries on end. Electricity, for example, had replaced open flame. “Chemistry has furnished the utensils, it has prepared the foods, and now it only remains for chemistry to make the foods themselves,” he argued.

Berthelot dared to dream that the laboratory could improve even human nature itself. Once people no longer needed to wage war over limited resources or engage in the soul-crushing “slaughter of beasts,” their character would increased in “sweetness and nobility.” “Perhaps,” he added, one fine day, synthetic or “spiritual” chemistry would even allow humans to alter their own “moral nature,” just as “material chemistry” altered “the conditions of [their] environment.”

________

Marcellin Berthelot fashioned his vision of science and sweetness at a moment that many at the time regarded as a watershed in human history. In the 890s, the world’s nations battled for control of dwindling global resources. Famines raged in India, Russia, and other parts of the world. Global population surged to new heights but so, too, did the number of humans living in cities, and as everyone knew, city folks relied on others to grow food on their behalf, and farmers worldwide struggled to keep up with demand.

In the U.S., then as now the world’s foodbasket, politicians, economists, and do-gooders bemoaned the crude state of American agriculture. Many people favored reorganizing farming so that it mimicked the factory, the better to supply the world’s foods.

So it's not surprising that as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, food was viewed universally as a crucial component of nation building, as important as navies, guns, and bullets.

Common theory linked food to national power and racial superiority: the quality and quantity of a nation’s diet predicted whether it would dominate or be dominated. In Europe, Great Britain, and the U. S., scientists like Berthelot raced to unravel the components of foodstuffs, obsessed with extracting every ounce of nutriment from every inch of soil or, better yet, from every test tube and microscope.

Of all the foods, meat reigned supreme. According to long-standing and widely shared theory, meat both denoted and endowed national power. Meat-rich diets had made Europeans and Americans masters of the planet, while “rice-eating” Japanese, Chinese, and “Hindoos,” as one typical essay phrased it, were an “inoffensive” collection of people from whom not much could be expected. (*2)

So meat there must be, if not from the farm then from the lab. “A lump of coal, a glass of water, and a whiff of atmosphere contained all the nutritive elements” of both bread and beefsteak, one writer observed in 1907. (*3) Science only needed to unravel the equation that would turn matter into meat.

Many applauded in 1912, when Jean Effront, a Belgian chemist, announced that he’d manufactured “artificial meat” from brewery and distillery wastes. (*4) Effront washed and compressed the wastes and doused them with sulfuric acid, rested the mixture a few days, and then added lime to neutralize the acid. Once the liquids evaporated: Voila! A product that contained the same “albuminous elements” as were produced in the human body by digested meat, but with three times the nutrional value of beef. Physicians who tested Effront’s Viandine, as he dubbed it, pronounced it “superior to beef.” Laboratory rats and an undernourished Belgian “workman” both gained weight and good health while eating it.

As to its taste, Effront was “silent” on that matter, but as one reporter noted, the point was moot. “It would be a hundred times better if foods were without odor or savor. For then we should eat exactly what we needed and would feel a great deal better. What seems certain is that such synthetic foods [are] nourishing.”

______________

Two days ago, Professor Mark Post, a Dutch-based scientist, unveiled the fruits of his own labor: laboratory-grown “hamburger.” Josh Schonwald, author of The Taste of Tomorrow: Dispatches from the Future of Food, said he missed “the fat,” but that “the general bite [felt] like a hamburger.” (*5)

And so the world turns. More or less. More than a century after Professor Berthelot waxed rhapsodic about meat from the lab, we humans face our own watershed moment. Is there sufficient food for the future? Is a meat-centric diet viable in a resource-scarce and environmentally fragile world? Even assuming that Professor Post can figure out how to mass produce petri dish burger, will people eat it? Or will this project go the way of, say, Golden Rice, a genetically modified rice designed to prevent blindness among malnourished children?

Will we citizens of the twenty-first century, like those a century ago, place our faith in science? Or will we demand solutions to hunger that look to the past rather than science for inspiration --- small, local, natural?

Only time will tell, but this much is sure: when it comes to food, and especially meat, there’s not much new under the sun.

__________________

*1: The interview with Berthelot is in Henry J. W. Dam, “Foods in the Year 2000,” McClure’s Magazine 3, no. 4 (September 1894): 303-12.

*2: “The Non-Beef-Eating Nations,” Saturday Evening Post, November 13, 1869, p. 8.

*3: Henry Smith Williams, “The Miracle-Workers: Modern Science in the Industrial World,” Everybody’s Magazine 17 (October 1907): 498.

*4: All the Effront quotations are from “Food From Waste Products,” Literary Digest 46 (January 4, 1913): 15-16. For a marvelous survey of how people have imagined and pondered foods and the future, see Warren Belasco, Meals To Come: A History of the Future of Food,” University of California Press, 2006.

*5: Quoted in "World's first lab-grown burger is eaten in London."

I just discovered that the entire text of the new book's Introduction is up at Amazon -- which means, hey, I can post it here, too. So, without further ado: The introduction to IN MEAT WE TRUST: AN UNEXPECTED HISTORY OF CARNIVORE AMERICA. (Complete, I might add, with some not-great photos of a few pages of the book.)

________________

Truly we may be called a carnivorous people,” wrote an anonymous American in 1841, a statement that is as accurate today as it was then. But to that general claim a twenty-first-century observer would likely add a host of caveats and modifiers: Although we Americans eat more meat than almost anyone else in the world, our meat-centric diets are killing us—or not, depending on whose opinion is consulted. Livestock production is bad for the environment—or not. The nation’s slaughterhouses churn out tainted meat and contribute to outbreaks of bacteria-related illnesses. Or not.

title page

The only thing commentators might agree on is this: in the early twenty-first century, battles over the production and consumption of meat are nearly as ferocious as those over, say, gun control and gay marriage. Why is that? Why do food activists want to ban the use of antibiotics, gestation stalls, and confinement in livestock production? Why have livestock producers, whether chicken growers, hog farmers, or cattle ranchers, turned to social media, blogs, and public relations campaigns to defend not just meat but their role in putting it on the nation’s tables? This book answers those questions and more by looking at the history of meat in America.

_____________

The American system of making meat is now, and has long been, spectacularly successful, producing immense quantities of meat at prices that nearly everyone can a afford—in 2011, 92 billion pounds of beef, pork, and poultry (about a quarter of which was exported to other countries). Moreover, measured by the surest sign of efficiency—seamless invisibility—ours is not just the largest but also the most successful meat-making apparatus in the world, so efficient that until recently, the entire infrastructure was like air: invisible. Out of sight, out of mind.

No more. For the past quarter-century, thoughtful critics have challenged the American way of meat. They’ve questioned our seemingly insatiable carnivorous appetite and the price we pay to satisfy it, from pollution of water and air to the dangers of high-speed slaughtering operations; from the industry’s reliance on pharmaceuticals to the use of land to raise food for animals rather than humans. In response, meat producers have reduced their use of antibiotics and other drugs; have abandoned cost- cutting products like Lean Finely Textured Beef (“pink slime”); have taken chickens out of cages and pregnant sows out of tiny gestation stalls. Men and women around the country have committed themselves to raising livestock and making meat in ways that hearken back to the pre-factory era. This book examines how we got from there to here.

_____________

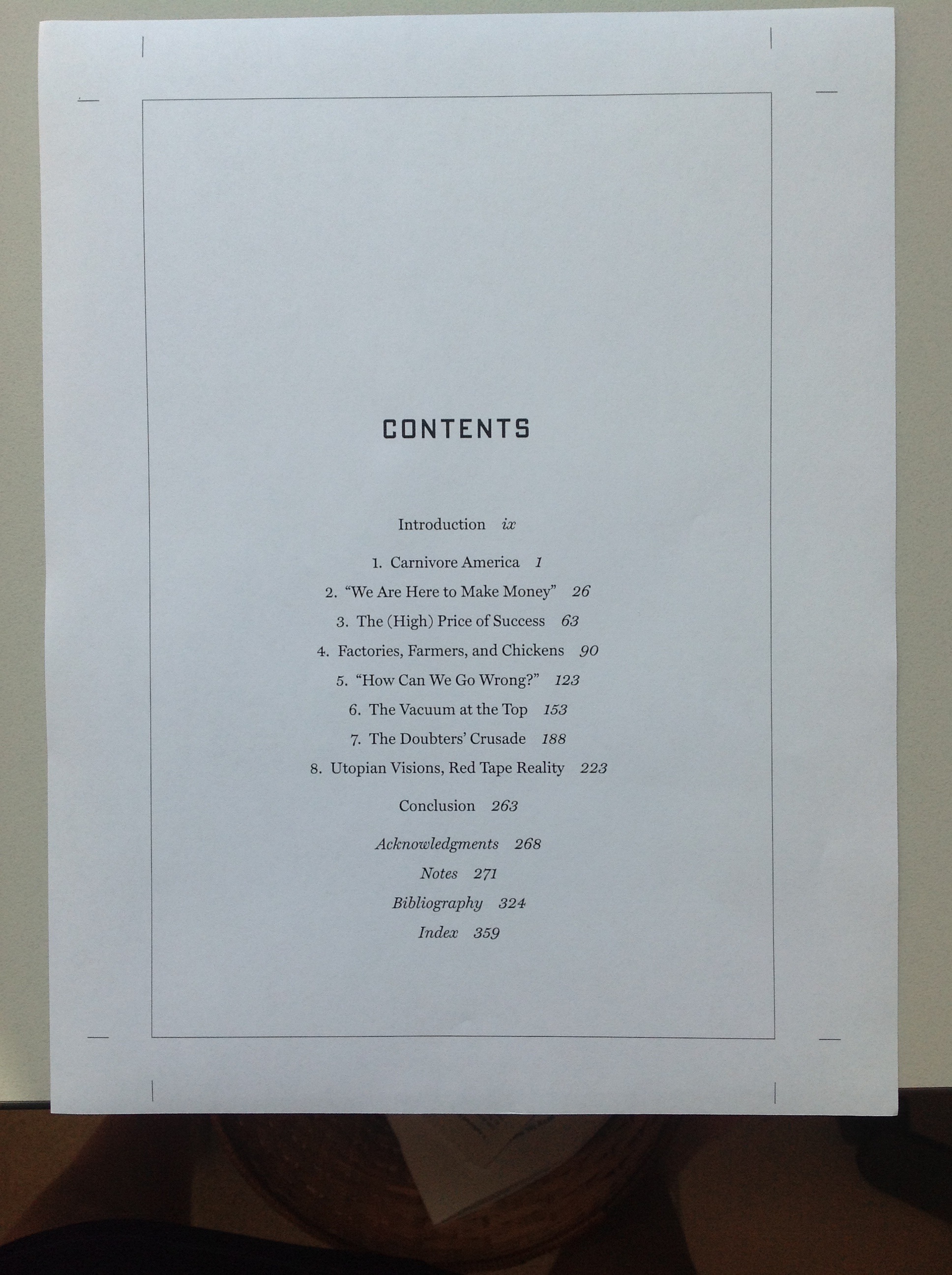

In recent years, books about food in general and meat in particular have abounded and in sufficient variety to suit every political palate. Few of them, however, examine the historical underpinnings of our food system. That’s particularly true of ones that focus on meat. Most are critical of the American way of meat and assert an explanation of our carnivorous culture and its flaws that goes (briefly) like this:

Back in the old days, farm families raised a mixture of live- stock and crops, and their hogs, cattle, and chickens grazed freely, eating natural diets. That Elysian idyll ended in the mid- to late twentieth century when corporations barged in and converted rural America into an industrial handmaiden of agribusiness. The corporate farmers moved livestock off pasture and into what is called confinement: from birth to death, animals are penned in large feedlots or small crates, often spending their entire lives indoors and on concrete, forced to eat diets rich in hormones and antibiotics. Eventually these cattle, hogs, and chickens, diseased and infested with bacteria, end up at the nation’s slaughterhouses (also controlled by agribusiness), where poorly paid employees (many of them illegal immigrants) working in dangerous conditions transform live animals into meat products. Agribusiness profits; the losers are family farmers who can’t compete with Big Ag’s ruthless devotion to profit, and consumers who are doomed to diets of tainted, tasteless beef, pork, and chicken.

TOC

I respect the critics and share their desire for change. But I disagree both with their explanation of how we got to where we are and with their reliance on vague assertions as a justification for social change, no matter how well intended — especially when many of those assertions lack substance and accuracy. Consider, for example, this counter narrative, which is rooted in historical fact:

The number of livestock farmers has declined significantly in the last seventy or so years, but many people abandoned livestock production for reasons that had nothing to do with agribusiness. From the 1940s on, agriculture suffered chronic labor shortages as millions of men and women left rural America for the advantages of city life. Those who stayed on the land embraced factorylike, confinement-based livestock production because doing so enabled them to maximize their output and their profits even as labor supplies dwindled. Confinement livestock systems were born on the family farm and only subsequently adopted by corporate producers in the 1970s.

We may not agree with the decisions that led to that state of affairs, and there’s good reason to abhor the consequences, but on one point we can surely agree: real people made real choices based on what was best for themselves and their families.

Make no mistake: the history of meat in America has been shaped by corporate players like Gustavus Swift, Christian gentleman and meat- packing titan, and good ol’ Arkansas boy Don Tyson, a chicken “farmer” who built one of the largest food-making companies in the world. But that history also includes millions of anonymous Americans living in both town and country who, over many generations, shaped a meat-supply system designed to accommodate urban populations, dwindling supplies of farmland, and, most important, consumers who insisted that farmers and meatpackers provide them with high-quality, low-cost meat.

______________

The tale chronicled here ranges from the crucial, formative colonial era to the early twenty-first century, although the bulk of the narrative focuses on the second half of the twentieth century. It answers important questions about meat’s role in our society. How did the colonial experience shape American attitudes to- ward meat? Why did Americans move the business of butchering out of small urban shops into immense, factorylike slaughter- houses? Why do Americans now eat so much chicken, and why, for many decades, did they eat so little? Why a factory model of farming? When and why did manure lagoons, feedlots, and antibiotics become tools for raising livestock? What is integrated livestock production and why should we care? Why is ours a “carnivore nation”? My hope is that this historical context will enrich the debate over the future of meat in America.

My many years engrossed in a study of meat’s American history led me to a surprising conclusion: meat is the culinary equivalent of gasoline. Think about what happens whenever gas prices rise above a vaguely defined “acceptable” level: we blame greedy corporations and imagine a future of apocalyptic poverty in which we’ll be unable to afford new TV sets or that pair of shoes we crave; instead, we’ll be forced to spend every dime (or so it seems) to fill the tank. But we pay up, cursing corporate greed as the pump’s ticker clicks away our hard-earned dollars. Then the price drops a few cents our routine, half-mile, gas-powered jaunts are once again affordable; and we rejoice. And because it’s so easy to blame corporations, few of us contemplate the morality and wisdom of using a car to travel a half-mile to pick up one item at a grocery store, which is what most of us do when gas prices are low.

So it is with meat. Most of us rarely think about it. After all, grocery store freezer and refrigerator cases are stuffed with it; burger- and chicken-centric restaurants abound; and nearly everyone can afford to eat meat whenever they want to. But when meat’s price rises above a (vaguely defined) acceptable level, tempers flare and consumers blame rich farmers, richer corporations, or government subsidy programs. We’re Americans, after all, and we’re entitled to meat. So we either pay up or stretch a pound of burger with rice or pasta (often by using an expensive processed product). Eventually the price of steak and bacon drops, and back to the meat counter we go with nary a thought about changing our diets or, more important, about the true cost of meat, the one that bar-coded price stickers don’t show.

Intro

That sense of entitlement is a crucial element of the history of meat in America. Price hikes as small as a penny a pound have inspired Americans to riot, trash butcher shops, and launch national meat boycotts. We Americans want what we want, but we rarely ponder the actual price or the irrationality of our desires. We demand cheap hamburger, but we don’t want the factory farms that make it possible. We want four-bedroom McMansions out in the semirural suburban fringe, but we raise hell when we sniff the presence of the nearby hog farm that provides affordable bacon. We want packages of precooked chicken and microwaveable sausages—and family farms too.

After years of working on this book, I’m convinced that we can’t have it all. But I also believe that if we understand that the past is different from the present, the future is ours to shape. My hope is that this book will help all of us understand how we got to where we are so that, if we are willing, we can imagine a different future and write a new history of meat in America.

A re-write of a piece I posted here a couple of years ago, and then re-wrote for Medium. _________________

A couple of years ago, someone I follow at Twitter (Adam Penenberg, to be precise) posted a link to an unintentionally hilarious but fascinating YouTube video from a 1994 episode of the “Today Show.”

The clip features the program’s then-anchors, Katie Couric and Bryant Gumbel, and “sub-anchor” Elizabeth Vargas, pondering the “internet” and the use of the @ symbol. They don’t get the latter, and they know the former is something big, but they’re not sure what.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JUs7iG1mNjI]

Hilarious, right? “What is the internet anyway?” “Internet is, uh, that massive computer network that’s becoming really big now.”

Indeed, the first time I saw this clip back in 2011, my quickie, knee-jerk Twitter response was “Howling!”

But I’m a historian, and even as I tweeted, I was already enjoying another, richer response to the clip: “Ooooh . . . . The possibilities!”

Think about it. The three anchors hosted what was then, and still is, one of the most popular news programs on television — “popular” in that it commanded a huge audience and so carried considerable heft. Every morning, millions of people tuned in to the “Today” show.

So you’d think that these three well-known, well-paid journalists would be, ya know, clued in on that thing called the internet, which was already changing every. single. aspect. of human existence.

(And was already being enjoyed by a large swath of fairly ordinary people. I mean, this was 1994, for god’s sake. By that time, even I, who was not particularly interested in techno-stuff, had owned a PC for more than a decade and I had an email account.)

And yet — none of those three had the foggiest. (*2)

Translation: one of the most profound moments in human history had begun, but had not yet been noticed by what we now call the “mainstream media” (MSM). (*3) (*4)

As a historian, I gotta tell you: the clip was a motherlode. (*5) It tripped my brain’s ignition switch and said organ began spewing questions.

And questions, my friends, are what we historians use to frame our work. They’re our footings and studs.

For example:

Why were the people launching this pivotal moment so far off the radar of mainstream journalists? (*6) And why was mainstream media oblivious about their work? (Those, by the way, are two quite different questions.)

How, if at all, did MSM’s ignorance of the extent/breadth/depth of the techno-shift shape the early history of the internet-and-web?

Did MSM’s obliviousness inadvertently foster internet/web pioneers’ fascination with/insistence on the much used/abused “information wants to be free” paradigm? (*7)

When, how, and why did Gumbel, Couric, and other journalistic powerhouses (and mock them all you will, but in the 1990s they were powerhouses) finally catch on? Who or what tipped them off?

And once aware, how did they, as journalists, then “shape” the story? How did their version of “what happened” differ from the narrative put forth by the internet/web pioneers?

I could rattle off questions indefinitely, but I’m not planning to research or write about any of this, so I’ll stop. (Hint to historians, grad students, etc.: Free topic! Have at it!)

But this example illustrates how historians go about their work. We react to a fact/moment/event by thinking: “Hmm. What’s up with that?”

And then our brains let rip with questions, and we start hunting for answers, and next thing we know, motherfuck, five, six, seven years have passed in pursuit of those answers. (*8)

It’s worth noting that the fuel that feeds and inspires those questions is the long-view, big-picture that is the historian’s mindset. Historians see life — i.e., the day-to-day weirdness of the human animal — in a Picasso-ish way: from simultaneous, multiple perspectives, and those perspectives are always elongated. We analyze life in terms of “time.” (*9)

And for better or for worse, we apply that point of view to damn near everything, including, in this case a seemingly trivial-bordering-on-silly YouTube video.

Here’s hoping that some other historian watched that clip and enjoyed the same reaction I did.

__________________________

1: For those who are wondering: no, I don’t write only and always about how historians do what they do. I’m using the topic to familiarize myself with Medium and its possibilities. My plan is to soon begin posting essays related to meat, food politics, and the like (because I just finished writing a history of meat in America and that’s The Big Stuff that’s on my mind).

*2: At the time I saw the clip, L. A. Lorek posted a Twitter link to a1994 article she’d written about the internet. Great companion piece.

3: Light bulb! Is this one reason that internet- and web-saturated folks today are so dismissive of said “mainstream media”? Can this clip help historians make sense of the history of that stance?

*4: That’s not necessarily a criticism, you know? We humans are rarely hyper-aware of Change with a capital C. (Although in the case of the YouTube clip, it’s telling that the three anchors didn’t “get” what the deal was with the www address being flashed on the screen. Someone at NBC “got it,” and enough so that the network already had a website. Again, that’s a useful and fascinating piece of information.)

*5: The Youtube clip falls into the category of a “primary source.” I wrote about those here.

*6: Obviously, some media were aware of what was going on. Indeed, some were founded specifically to report/record it; think, for example,Wired. But — apparently the anchors of the most popular daytime TV news program hadn’t gotten the memo.

*7: Oh, the “information wants to be free” thing. Oh oh oh. The phrase is part of a statement that Stewart Brand made in 1984. Been used and abused ever since. Now THERE is a topic that deserves a serious historian’s serious attention.

*8: If we’re lucky enough to have the time and wherewithal, we write a book about what we’ve learned; we tell the story of “what happened.” And if our luck holds, we publish that book for a large audience.

*9: Frankly, it’s a bit of a curse. The teensiest, most random, and apparently trivial thing becomes fodder for my reverse-telescope, time-focused lens. Maddening. (Although I wouldn’t give it up.)

Another take on how I do what I do. Parts of this ran here several years ago. Again, for those following along: I'm experimenting with different formats and concepts, and no, I'm still not sure how this will all shake out.

Several years ago, a professor at a nearby university asked me to speak to her class; the required readings in the course included Ambitious Brew, my history of beer in America. I talked for fifteen or twenty minutes and then asked for questions (because audience questions are infinitely more interesting than whatever I have to say).

Up shot a hand and a young woman asked an obvious, intelligent question (which I’m here paraphrasing):

In the first chapter, you describe Phillip Best hauling his new brewing vat through the streets of Milwaukee. But that scene reads like a story; like fiction rather than fact. How do you know that’s what happened? Why should we believe you?

I was glad she asked. So glad. Because that question gets to the heart of what historians do.

For those who don’t have a copy of the book at hand, the scene she referred to unfolds on pp. 1-3. (*1) The setting is Milwaukee in 1844 and at its center is Phillip Best, the man who founded what eventually became Pabst Brewing Company. He and his family had recently emigrated to the U. S. and Milwaukee, and he was trying to find someone to fabricate a brew vat for the Bests’ new brewhouse. Here’s that scene:

Late summer, 1844. Milwaukee, Wisconsin Territory. Phillip Best elbowed his way along plank walkways jammed with barrels, boxes, pushcarts, and people. He was headed for the canal, or the “Water Power,” as locals called it, a mile-long millrace powered by a tree-trunk-and-gravel dam on the Milwaukee River. Plank docks punctuated its tumbling flow and small manufactories–a few mills, a handful of smithies and wheelwrights, a tannery or two–lined its length. Best was searching for a particular business as he pushed his way past more carts and crates, and dodged horses pulling wagons along the dirt street and laborers shouldering newly hewn planks and bags of freshly milled grain. He had only been in the United States a few weeks and Milwaukee’s bustle marked a sharp contrast to the drowsy German village where he and his three brothers had worked for their father, Jacob, Sr., a brewer and vintner.

Phillip finally arrived at the shop owned by A. J. Langworthy, metal worker and ironmonger. He presented himself to the proprietor and explained that he needed a boiler–a copper vat–for his family’s new brewing business. Would Langworthy fabricate it for them? The metalworker shook his head. No. “I [am] familiar with their construction,” he explained to Best, “. . . but I [dislike] very much to have the noisy things around, and [I do] not wish to do so.

Eventually Phillip persuaded Langworthy to make the vat, and a few weeks later, he returned to fetch the finished product:

It’s not clear how Phillip transported his treasure the half mile or so from Langworthy’s shop to the family’s brewhouse. Perhaps his new friend provided delivery. Perhaps Phillip persuaded an idling wagoner to haul the vat on the promise of free beer. Perhaps one or more of his three brothers accompanied him, and they and their burden staggered through Kilbourntown–the German west side of Milwaukee–and up the Chestnut Street hill. But eventually the vat made its way to the Bests’ property–the location of Best and Company and the foundation of their American adventure.

Yes, the student asked a good question: I wasn’t there. How in the world did I know what happened? Is this fact or fiction? If it’s the latter, why should my work as a historian be trusted?

Here’s how I answered her question: That scene was based on both fact and common sense.

Consider my description of Phillip’s journey to Langworthy’s shop.

I knew, based on evidence I’d found, that in the summer of 1844, the Best family had almost no money. They’d only just arrived in America and had not yet launched their business. According to an account I read, the family had spent nearly all its available cash buying a piece of property on which to build a small brewhouse. (*2) I knew they owned a horse (they relied on it to power their grindstone). (I learned about the horse from a letter Best wrote.)

But horses were (and are) expensive, and at the time, most people (and certainly the cash-poor like Best) walked rather than rode. Moreover, in 1844, Milwaukee, a relatively young town, had no form of public transportation. (At the time, Wisconsin was a territory, not a state. This was frontier.)

I also knew that the Best brewhouse was only about a half mile from Langworthy’s shop, an easy walk. How did I know? I found an ad for Langworthy’s business in a Milwaukee newspaper, an ad that included his address. Using a c. 1850 map of Milwaukee (the earliest map I could find), I located both the Bests’ property and Langworthy’s shop. Then I consulted a current map of Milwaukee to calculate the distance from the brewery to the shop. When I visited Milwaukee to conduct research at the library there, I also walked the route myself.

How did I know that Phillip’s walk took him past the millrace, the docks, the tanneries, and so forth? I reconstructed the town’s landscape by reading eyewitness descriptions of Milwaukee as it appeared in 1844, including letters, diaries, newspapers, and government documents.

Armed with what I’d learned, I was able to write an accurate description of Phillip’s trek from home to the business district, one based on multiple, verifiable facts.

But how do I know which sources are reliable, and which aren’t? When I’m prowling through the primary sources — letters, diaries, and so forth — I compare one source with another, hunting for multiple verifications of facts. In this case, I read many descriptions of Milwaukee, ones written by people living there at the time. I compared those with items delineated on that c. 1850 map, and with contemporary illustrations of the land

I also used secondary sources — books and articles written by other scholars. In this case, for example, I consulted several histories of Milwaukee.

But I only employ secondary sources after I’ve determined that they’re reliable; that I can trust their accuracy. As an example, let’s look at another excerpt from the book’s opening scene:

Phillip finally arrived at the shop owned by A. J. Langworthy, metal worker and ironmonger. He presented himself to the proprietor and explained that he needed a boiler–a copper vat–for his family’s new brewing business. Would Langworthy fabricate it for them? The metalworker shook his head. No. “I [am] familiar with their construction,” he explained to Best, “. . . but I [dislike] very much to have the noisy things around, and [I do] not wish to do so.”

Here I relied on an eyewitness account of Best’s visit to Langworthy’s shop: Langworthy himself. Several decades after the fact, the iron monger recounted the episode to a local newspaper reporter. (*3) (By the time Langworthy told the story to a reporter, the company that Phillip founded was the world’s largest brewery, although its then-owner had changed the name to Pabst Brewing Company.)

I found that interview in a history of Pabst Brewing written by another historian, Thomas Cochran. (Cochran’s history was thus a secondary source, but one based on primary sources.) (Here’s hoping you’re not totally confused.) I quoted Langworthy’s words, citing Cochran’s book as my source.

In this case, and rather unusually for me, I didn’t read the actual newspaper article. (*4) But I knew that I could trust Cochran: I was familiar with his career and had read other books by him. I was also able to verify many of the other sources he used in his book.(*5)

I trusted, in other words, that Cochran’s secondary account (his history of Pabst Brewing Company) was a reliable source of information and that the newspaper article he’d quoted was a reliable primary source. I was comfortable quoting Langworthy’s account of the encounter.

That’s an important part of what historians do: We don’t accept evidence at face value. We have to decide whether a piece of evidence is reliable and accurate. We have to decide whether we trust that bit of evidence. And sometimes, we don’t.

Here’s an example, also from Ambitious Brew, where I rejected the veracity of evidence. (This one is from pp. 102-103). The context for this excerpt is the “beer wars” of the 1890s and brewers’ efforts to control industry competition. Here I recounted an alleged encounter that took place between Adolphus Busch, who for many years headed Anheuser-Busch, and a group of rival brewers:

In one contest, according to Adolphus Busch’s grandson August “Gus” Busch, Jr., a group of small New Orleans brewers resisted Adolphus’s efforts to control that city’s trade. A prolonged struggled drove the barrel price well below the profit zone. Finally Adolphus ended the conflict by informing the men that he planned to “control the price of beer for the next 25 years. . . whatever goddamn price I put on my beer, you go up [or down] the same goddamn price.”

Many decades later, Gus Busch, who claimed to have witnessed the encounter, recounted the tale as evidence of his grandfather’s wily ways and masterful control over lesser men. If the Busches invaded, say, Peoria, they could afford to wait out the competition; could afford to absorb the losses incurred by selling barrels at cost. Small local breweries could not. More often than not, the conqueror drove the conquered into bankruptcy.

I found this anecdote in Under the Influence, a book about the Busch family written by two St. Louis journalists, Peter Hernon and Terry Ganey. Hernon and Ganey interviewed Gus Busch, and he told them this story. (*6)

As soon as I read the anecdote, I knew it wasn’t true, at least not as Gus Busch recounted it. (Notice that in the excerpt from my book, I included a modifier: “according to Adolphus Busch’s grandson August “Gus” Busch, Jr.. . . .”) So why did I include it in my book? Here’s the next paragraph in the book (from p. 103):

The anecdote, though it captures the brutality of the struggle, is most likely apocryphal. The most ferocious beer wars unfolded in the two decades prior to Gussie’s birth in 1899. Adolphus’s health failed in 1906, leaving him frail and wheelchair-bound; from then until his death in 1913, he spent most of his time in California or Europe. Even assuming the event took place as late as, say, 1910, when Gussie would have been eleven years old, Adolphus would not have been involved and his grandson too young to comprehend the grown-ups’ conversation, let alone remember it accurately some seventy-five years later. More likely the tale evolved over the years as part of the mythology that surrounded a family of successful men with over-sized personalities.

This is an important part of the historian’s task: Sifting through evidence to find the most reliable, verifiable pieces of information. I examine multiple sources of information and different kinds of evidence. Only then do I decide which evidence is reliable and which is not. (*7)

Is this art or craft? In my opinion (based on 25-plus years experience), it’s more craft than art. Historians learn to use and trust evidence through experience, trial-and-error, and the wisdom acquired from both. Does that mean I’m always “right”? No. But I make the best judgments I can, using the evidence at hand.

Finally, to return to where I started and the student in that class I visited: She commented that because the book read like a novel —- that it read like fiction rather than fact — she was skeptical about its contents.

My response was: Thank you!

That’s a compliment. I want my books to “read” like a novel — not in the sense that the content is fiction, but in the sense that the narrative has pace, action, “characters,” and a “story”-like structure: a beginning, a middle, and an end. (*8)

Why? Because that’s a useful way to present the sweep of history and to persuade readers that “history” is more than a boring string of facts. History is fascinating, and one way to understand historical events is by seeing them through the lives and eyes of the people who participated in them.

In the case of the beer book, for example, the first chapter covers an array of significant historical events and trends: the impact of immigration in mid-nineteenth-century America, including riots and battles between immigrants and “natives”; the prohibition movement of the 1850s; and Americans’ attitudes toward alcohol, to name just a few.

Those are Big Topics. I brought them down to earth and anchored their heft by attaching them to a real person, in this case Phillip Best. Surely it was more interesting to read about his stroll through Milwaukee than to read, say, a list of statistics about immigration.

That’s true throughout the book: I populated the “story” with real people, using their own words whenever possible. I also avoided professional jargon; I used active rather than passive verbs; I described scenery and surroundings.

It helped that I enjoyed access to a built-in cast of characters: Phillip Best anchored the Big Topic events of Chapter One. Once he exited the stage, Frederick Pabst (Phillip’s son-in-law) and Adolphus Busch entered. They carried the story for the next two chapters.

In Chapter Four, they’re around part of the time, but are joined by a man who was instrumental in launching the Anti-Saloon League, the organization that drove the push toward Prohibition in the 1890s and early twentieth century. And, because the Busch family multiplied I had plenty of “characters” to carry the narrative from Prohibition to the 1970s.

I struck gold for the book’s final two chapters, where I examine the craft beer “revolution” of the 1980s and 1990s. Many of the people who launched that industry are still alive, and I enjoyed an abundance of “actors” for my drama.

Throughout, however, I stuck to facts. If I speculated about an event, I was careful to say that “perhaps” something happened. Consider this final example, again from Chapter One, when Langworthy learns that Phillip Best does not have enough money to pay for the brewvat.

What happened next is a credit to A. J. Langworthy’s generosity and Phillip Best’s integrity. Langworthy was but a few years older than Phillip. Like Phillip, he had left the security of the familiar–in his case, New York–for the adventure and gamble of a new life on the frontier. Perhaps he glanced through the door at the mad rush of people and goods flowing past unabated from daylight to dusk. He was no fool; he understood that business out in the territories would always be more fraught with risk than back in the settled east. But what was life for if not to embrace some of its uncertainty? [Langworthy let Best take the vat and to pay for it once the family began earning money.]

I obviously don’t know if Langworthy looked out at people passing by on the wooden walkway that ran along the front of his shop. So I said that “perhaps” he did so.

But the rest of it? I am confident, based on factual evidence, that I captured the essence of the encounter: Langworthy had abandoned the security of the urban eastern United States and moved to the frontier of Wisconsin Territory. In doing so, he embraced life’s uncertainty. He knew that Phillip’s family had done the same, leaving Europe for the United States. I also knew that he let Phillip take the vat, and allowed him to pay the debt later, an act that surely stemmed from Langworthy’s opinion about the man standing before him.

In short, I believed, based on the facts, that Langworthy understood the nature of risk and uncertainty — and empathized with Phillip’s situation.

So. Historians trade in facts. They learn to trust their judgment about evidence and how to use it. They employ that evidence to construct an engaging narrative, one that is centered around the lives of real people. If the historian telling the “story” is honest and careful and thorough, readers will know that they can trust that the “story” is true.

That’s my story, anyway, and I’m stickin’ to it.

___________________

*1: Hey! Whatsa mattah witch you? GET ONE. (Kidding, people, kidding.) (Okay, sort of.) (Yes, I have a mercenary side. Every author does, ‘cause we ain’t doin’ this for free, you know?)

*2: The brewhouse, by the way, was small: perhaps twenty feet by twenty feet. That’s all they could afford.

*3: Yes, by the time Langworthy recounted that moment to a reporter, he would have been an old man. But he’d likely told the story many times, if only because Best himself went on to become an important and well-known man.

*4: I don’t remember now why I didn’t read the actual newspaper account (it’s been ten years since I worked with those sources). It may have come from a newspaper for which there are no longer copies. (I don’t have a copy of Cochran’s book in front of me so I can’t check to see where the interview was published. Sorry!)

*5: Cochran had a long and respected career as an economic historian. Indeed, he was and is regarded as one of the 20th century’s most important scholars in that field. He wrote his history of Pabst Brewing with the blessings and cooperation of Gustav and Fred, Jr., the sons of Frederick Pabst. Cochran also had access to hundreds of documents that have since been lost or destroyed. As you might imagine, I was, and am, grateful for Cochran’s careful and thorough work as a historian.

*6: Gus was an old man by the time Hernon and Ganey interviewed him in the late 1980s; he died in 1989.

*7: As I conducted my own research for the beer book, I constantly compared what I found to the Ganey/Hernon version of the Busch family. Based on what I knew, I concluded that their book was not a reliable source of information. That assessment isn’t as unkind as it sounds: The men are journalists, not historians, and they had a different agenda for their book than I did for mine.

*8: Non-fiction “fictional histories” abound. (By fictional history, I mean works of non-fiction, NOT historical fiction.) These are cases where an author writes a history of Topic X, but mixes fact and fiction in order to make the story more interesting. For example, someone who writes fictional history might supply his/her “characters” with dialogue, the way a novelist writes dialogue for one of her characters. That’s not how I work, but some authors are more interested in “writing” than in doing history, and for them, it’s easier to create facts and dialogue to suit the purposes of plot and pacing than it is to work within a framework of fact. No surprise, these plot-driven fictional histories resonate with readers. Bestseller non-fiction lists typically include at least one fictional history. Hey, more power to ‘em. Those authors are making a lot more money than I am! (*9)

* 9: The only thing that bugs me about the authors of non-fiction, fictional histories is when they’re identified as “historians.” They’re not historians. They’re writers, most of them damn good ones.(*10)

*10: Yes, I just inserted a footnote within a footnote. And then a footnote within a footnote within a footnote. I’ll stop now. (Footnotes: The historian’s drug of choice.)

Website of Maureen Ogle, author and historian. Books include Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer; In Meat We Trust: An Unexpected History of Carnivore America; and Key West: History of An Island of Dreams.

Powered by Squarespace